By Douglas V. Gibbs

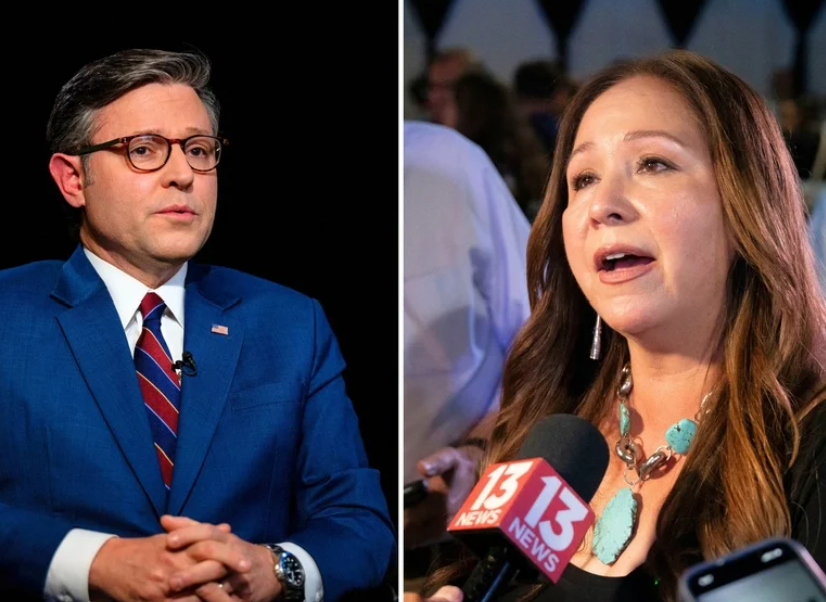

Adelita Grijalva won a special election on September 23, 2025 for Arizona’s 7th Congressional District, succeeding her late father Raul Grijalva. She, like her father, is a hard-core leftist Democrat, and so far Republican leadership in the House of Representatives has refused to swear her in. The battle has drawn attention, and has led to Arizona suing Speaker Mike Johnson over it. The lawsuit is no surprise since the Arizona attorney general has been threatening legal action all along. The optics for Republicans look very partisan, and their reasons for not seating Grijalva politically motivated. House Speaker Mike Johnson states that the oath will be administered when the House resumes full legislative business and at the moment their efforts are centered around resolving the current government shutdown. The lawsuit, Grivalva v. Johnson, was filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, and is more of a scare tactic than anything, with the hopes that a lower federal court will force Congress to act.

For me, the issue in play here is that if the courts were to remain consistent with past cases, they will dismiss the case using the “political question” argument which disallows courts from intervening in matters involving Congress due to the separation of powers concept. Cases in which the “political question” angle has been used by the federal courts in conjunction with the separation of powers doctrine to both limit and justify congressional actions leading to a dismissal of the case includes:

- Seila v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2020)

- Constitution Association v. Kamala Devi Harris (2020)

- Zubik v. Burwell (2016)

- Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (2010)

- Humphrey’s Executor v. United States (1935)

If the federal courts do not use the political question argument to dismiss this case, and instead rule that Speaker Johnson is in violation of the Constitution or some law on the books the courts would be in violation of past precedent set by the federal court system and would also violate the fact that in Article I, Section 5 of the Constitution each House of Congress is tasked with being its own judge of election, returns, and qualifications of its own members and may determine its own rules of its proceedings. In short, regardless of what the courts want to say, Speaker Johnson and the Republican majority in the House of Representatives is fully constitutionally authorized to hold off Grijalva being seated. Granted, I don’t see the reasoning behind it, and I don’t fully agree with Speaker Johnson’s action, but he is constitutionally permitted to take that action, or should I say “inaction.”

When it comes to the legal case, while I believe it should be dismissed on the grounds of “political question,” the Democrats believe they also have past Supreme Court decisions supporting their case which would disallow the House from excluding a duly elected and qualified member; one case being Powell v. McCormack (1969), which held that the House cannot use internal rules to deny or delay seating of a qualified member.

Johnson’s team could argue that the House, not the executive, the member-elect, nor the courts may decide when it is “in-session” for formal acts, a position known as the procedural sovereignty argument. It’s not a case of denying credentials; it’s a case of waiting until things are back in action once the government shutdown is over.

Having not been sworn in, yet, Grijalva cannot officially perform many of the functions of a sitting U.S. Representative: staffing, constituent services, voting, or moving into her congressional office. Granted, since the House of Representatives is in a pro-forma session (in session, but without enough members present to fulfill the quorum requirement, a condition allowed by the first paragraph of Article I, Section 5 of the Constitution, she would not be able to vote anyway. However, as she has stated in interviews, by not being seated she is more like a tourist in Washington D.C. at the moment.

As a constitutional originalist (of which I am before I am a Republican) and a lifelong Republican, I normally stand shoulder to shoulder with my GOP brethren, especially since the establishment RINOs have been on the run thanks to the appearance of President Donald Trump on the scene. But, I am not so sure in this case. I fully agree that Speaker Johnson’s delay in swearing in Adelita Grijalva has nothing to do with the Epstein files controversy as the Democrats have been arguing. However, agreement on motive or the fact that he can constitutionally does not translate to historical justification or my opinion that in the end it accomplishes nothing.

The reality is that in the past, including newly elected Republicans, the swearing in has been quick, even during pro-forma sessions. I get it, at the moment the Republican majority is slim. Currently there are 219 Republicans and 212 Democrats with four vacancies and the minimum needed to pass many pieces of legislation is 218 seats which means the GOP needs all hands on deck and no more than one defection if they are to pass legislation when no Democrat is willing to cross the aisle on a vote. With such a narrow margin and the need for near-unanimous support from its members, even one more Democratic vote can shift what procedural maneuvers are possible, such as collecting signatures for discharge petitions or forcing certain floor actions.

Johnson has argued that in past situations members were sworn in on scheduled days when the House was called into session, characterizing Grijalva’s case as being different because the House is “out of session” due to the government shutdown. Except, the House is not out of session, it is in pro-forma session. Johnson argues that until they are in full session they don’t have to seat Grijalva and he states that historical precedent is on his side… even though it’s not.

To research the history that Johnson claims is on his side, I first went to the first six presidencies, known as the Founding Father Presidencies.

- George Washington (1789-1797): The First Congress in 1789 seated members as soon as they arrived with proper credentials. Some arrived late due to travel delays, and the Clerk administered the oath individually upon arrival, not waiting for a future “full session.” There were no cases of a qualified member being kept from being sworn in.

- John Adams (1797-1801): The Fifth Congress in 1797 swore in replacements from special elections as soon as their credentials reached the House, according to the Annals of Congress, 5th Congress. Records show that members were sworn on the same day credentials were presented.

- Thomas Jefferson (1801-1809): the Seventh Congress in 1801 also followed the immediate-swearing in precedent. Matthew Lyons of Vermont was reelected while in jail, a victim of the Sedition Act for speaking out against John Adams, but once released from jail, even though the election hung in the balance on the floor of the House of Representatives, he was sworn in at once despite his imprisonment controversy; demonstrating the House prioritized representation of constituents over politics. No delays based on recesses or political disputes approaching or during Jefferson’s presidency appears in the records.

- James Madison (1809-1817): During the War of 1812 the reality of travel delays saw that members often arrived days or weeks after the start of session. Each time, the Clerk administered the oath upon their arrival; even when the House was not in “regular session.” No instance of postponing a qualified member’s swearing-in until full session exists in any of the records.

- James Monroe (1817-1825): During Monroe’s presidency there were several special elections and with each new member the swearing-in was given immediately upon arrival according to the Annals of Congress.

- John Quincy Adams (1825-1829): The pattern continued. Once the member arrived and credentials were presented, the Clerk administered the oath. The only delays occurred when an election was contested, not when the seat was vacant for administrative or political reasons.

The conclusion is that with every Founding Father presidency there were no delays for political reasons, giving no historical precedent for Johnson’s action.

What about since the Founding Era?

In 1794, Albert Gallatin of Pennsylvania was excluded because he had not met the requirement in Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution regarding citizenship duration. In 1807, John Smith of Ohio was refused to be seated due to allegations of aiding Aaron Burr in his alleged treasonous activities – of which were later dismissed. During the late 1800s there were dozens of disputed elections which led to delays, but none of them for purely political reasons or the argument that the House was not in full session.

A part of the problem is refusing to seat Grijalva actually accomplishes nothing. She can’t vote until they are in full session, anyway. But it does keep her from being able to get her congressional things in order, i.e. staffing, getting into her office, and so forth.

Yes, technically the House controls its own proceedings, and yes the courts have no business dictating to either House of Congress how to handle their own proceedings (which gets us back to that “political question” argument). But, the truth is that, as much as I respect Speaker Johnson and the difficult position he faces during a government shutdown, as stated earlier I can find no historical defense for withholding the oath from a duly elected, certified member of the United States House of Representatives. From the Founding era through the early Republic, every historical precedent shows that once credentials are verified and the election uncontested, the House has a duty to seat the member immediately. The Founders did not design a Congress where political timing or convenience could override the people’s right to representation in the House of Representatives. Yes, technically from a constitutional point of view Johnson “can” refuse to administer the oath to Grijalva at this junction, but that doesn’t mean he “should.”

Even if Johnson’s intention is procedural, the result is that the voters of Arizona’s 7th District are, for now, voiceless in the people’s chamber. That should trouble all of us who believe in constitutional fidelity over party expedience. In the end, while the lawsuit against Johnson should be dismissed, and he should have seated Adelita Grijalva in the first place, I have a feeling this situation won’t be over until the Democrats give in on the government shutdown.

— Political Pistachio Conservative News and Commentary