By Douglas V. Gibbs

The United States Constitution was designed to include the aim of balancing power through a proper distribution of it. Limited government, sometimes called small government, means that authority is confined to its rightful boundaries, leaving local issues to local governments and communities. Thomas Jefferson described this principle as laissez-faire, allowing matters to take their natural course without unnecessary interference.

From the beginning, the federal government was tasked with handling issues pertinent to the union, such as foreign trade, war, and maritime law. States retained authority over internal matters directly affecting their resident. A handful of domestic concerns, such as interstate disputes and the postal service, were entrusted to the federal government because they were essential to preserving and promoting the union. At every level, care was taken to ensure localism remained intact. State constitutions mirrored this design, reserving local issues for counties and municipalities.

America was not established as a pure democracy but as a republic, carefully structured to balance competing interests. The House of Representatives, like one half of the state legislatures, gave population centers a stronger voice through democratic elections. Yet the U.S. Senate and corresponding state senates were designed differently, ensuring rural and less populated areas also had a strong voice. This arrangement created a natural check and balance, preventing city folk’s representatives from telling the farmers how to farm without the farmers having a voice in the process.

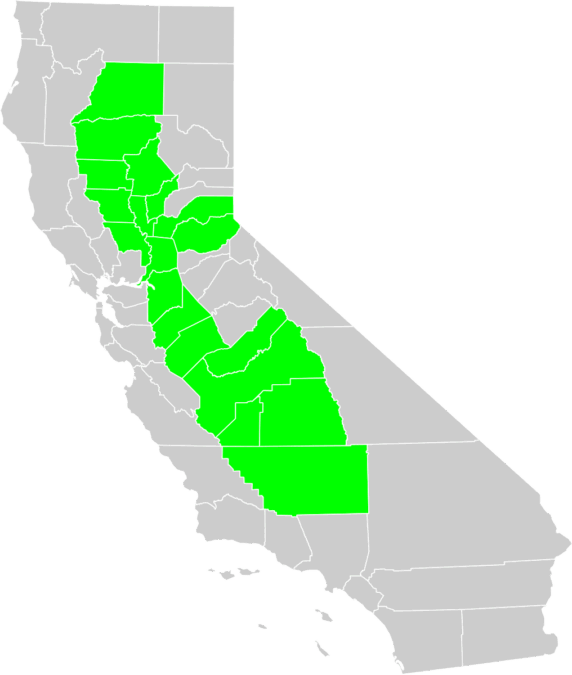

Over time, however, this balance has eroded thanks to mechanisms like the Seventeenth Amendment and Reynolds v. Sims (1964). A striking example of the consequence of becoming more democratic is California’s Central Valley water controversy. As our country and the states have drifted toward pure democracy politicians representing heavily populated urban areas increased their numbers in the legislature, dominating over the rural voice. As a result, these particular politicians have increasingly adopted collectivist approaches, sidelining the individualistic localism that defined America’s early generations.

Nowhere is this tension clearer than in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. Water, a vital resource, has become the battleground. Progressive leaders in Sacramento argue that environmental concerns justify restricting water supplies to farming communities. Farmers counter that these restrictions starve the Central Valley of the water essential to its role as one of the nation’s most productive agricultural regions. The Valley produces a significant share of America’s fruits, vegetables, and nuts, yet its farmers face man-made scarcity. They argue that northern water supplies could be diverted as they once were, but regulations and claims of scarcity prevent it. The consequences ripple outward: shuttered schools, closed businesses, and weakened communities.

Farmers see themselves as stewards of both the land and their communities, advocating for policies that allow them to thrive. They view Sacramento’s environmental regulations and water rights restrictions as unconstitutional government overreach. Their opponents, however, insist that protecting species such as the Delta Smelt, incidentally not indigenous to the region, must take precedence, even when human needs are urgent. This clash underscores the deeper divide: urban politicians blaming rural communities for water issues, while simultaneously dismantling dams and refusing to build new infrastructure.

Conservatives argue that the solution is straightforward: release more water into the Central Valley and build the infrastructure necessary to sustain both agriculture and safety. The stakes extend beyond farming. The Palisades Fire, with its dry reservoirs and empty hydrants, revealed how inadequate water allocation endangers lives. Proper infrastructure is not merely about crops. It is about survival.

The Constitution’s genius lay in its balance between federal and state, urban and rural, majority and minority. California’s water wars illustrate what happens when that balance is abandoned. Localism, once the cornerstone of American governance, is being replaced by collectivism, leaving vital communities vulnerable. Restoring constitutional principles of limited government and distributed authority may be the only way to resolve conflicts like those in the Central Valley. After all, water is not just a resource, it is in many ways a part of a much larger list of issues: life, liberty, and the foundation of prosperity.

— Political Pistachio Conservative News and Commentary